A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his own image

Joan Didion

When we think of circular economy, we commonly associate it with large industrial transformation processes and with the progressive change of production models through pilot projects and innovative success stories. On the other hand, the idea of circularity also drains into the habits and daily life of people, valuing the domestic practices of reuse, recycling, responsible consumption and resource optimization. The consumer must therefore assume his role within the production system as a structural part of his daily life. But the system is not reduced to the simple producer-consumer binomial. When the consumer takes the ink cartridge to a collection point conveniently located near his home or workplace, the consumer is participating in the distribution system. The consumer takes on another role in the process, assuming part of the logistics operations within his daily routine. But for that to happen, the collection center must be strategically located where the consumer can easily incorporate it into his or her daily life.

The transition to a circular model goes beyond an ink cartridge; ideally, this logic should be applied homogeneously to everything we consume. Many of the different steps in the collection, treatment and reuse processes occur at an intermediate scale, outside both domestic spaces and large production centers. This intermediate scale is the neighborhood scale where proximity relations facilitate integration between productive flows and daily habits. However, textiles, foodstuffs, electronic devices and furniture follow different circular systems that involve technical processes particular to each product. In this sense, if we want to incorporate circular habits we must equip our neighborhoods with a technical support infrastructure to the production processes.

Infrastructures “in between”

Moving beyond the top-down dimensions of production or the bottom-up dimensions of the conscious consumer, it is absolutely crucial to work on intermediate scale infrastructures where both systems merge in collaborative models. Partnerships between different actors (community, economic and institutional) is key to the implementation and operationalization of this network of infrastructures. Their productive vocation support communities by generating opportunities for capacity building, employment, inclusion of vulnerable groups and the creation of meeting spaces.

The circular transition is based on the capacity of a community’s living spaces to incorporate the infrastructures that support the different steps of the productive process. Urban renewal operations should therefore seek to systematically incorporate spaces that allow the development of this type of productive practices as complementary elements to the traditional network of facilities and public spaces. This is a great challenge, especially in existing urban fabrics where market dynamics and traditional real estate management models make it difficult to provide spaces for such practices.

At first glance it is hard to imagine how a residual space in our neighborhood, be it a clandestine garbage dump or an abandoned warehouse at the bottom of an internal courtyard, can be adapted to incorporate ambitious dynamics, which in time can offer a spatial quality that contributes to the creation of a community and is also feasible at the operational level. This leads us to think about the fundamental difference between a space and a place.

A place for everything and everything in its place

According to Marc Augé, a place (as opposed to what he defines as Non-Place) can be defined as a space around which an identity is built, which has a history, which forms part of a collective imaginary and which belongs to a spatial and cultural context. Therefore, transforming a space into a place requires a collective process of appropriation and memory creation.

It is around this principle that the concept of Placemaking is built on, as a practice that seeks the progressive generation of places. The Project for Public Spaces (PPS) initiative defines Placemaking as a method that “invites people to collectively reimagine and reinvent urban spaces as the heart of every community to maximize shared value. It facilitates creative patterns of use, considering the physical, cultural, and social identities of a place, as well as the needs of different users”.

Placemaking is essentially a process, which seeks to reactivate dysfunctional urban spaces, creating places of collective appropriation by and for the community. Placemaking implies very effective bottom-up democratic processes as strategies of inclusion and citizen participation.

Placemaking represents the field of action that links the two extremes of the spectrum by creating dynamics of interdependence between institutions and civil society. This means to attribute a share of responsibility to the many actors who build the city from specific places and communities and ensuring that they have the means and capacities to fulfill this responsibility.

But with great responsibilities also come great powers. The transition to a circular model should not be conceived as an obligation to be fulfilled but as a systematic instrument for the empowerment of individuals. Empowered communities are better prepared to react collectively to change, always looking out for the well-being and quality of life of those who live in them.

Placemaking is therefore strategic to bridge place-based challenges and societal ambitions. It is crucial to create opportunities to include placemaking within the formal urban planning and renewal processes, to raise support for community scale practices and to incorporate placemaking in the methodological approach to spatial projects.

Author: Diego Luna Quintanilla, Senior Project Leader at BUUR Part of Sweco and co-founder of Cakri asbl

Contributions by :

- Sedaile Mejias, urbanist architect at BUUR Part of Sweco and co-founder of Cakri asbl

- Anaïs De Keijser, Country Project Leader d’Urban Insights at Sweco Belgium

- Hélène Rillaerts, Team manager architect at BUUR Part of Sweco and Board member of ecobuild.brussels

This article is based on a White Paper that will be publish on the knowledge sharing platform Urban Insight by Sweco.

Picture: Reference Case : Pilot project De Potterij / BUUR Part of Sweco + Miss Miyagi [2]

Read also: What future for sustainable construction?; Materatek, a space for achieving your sustainable ambitions; A word from the chairwoman; From waste to art

[1] S²Cities Programme (https://s2cities.org/)

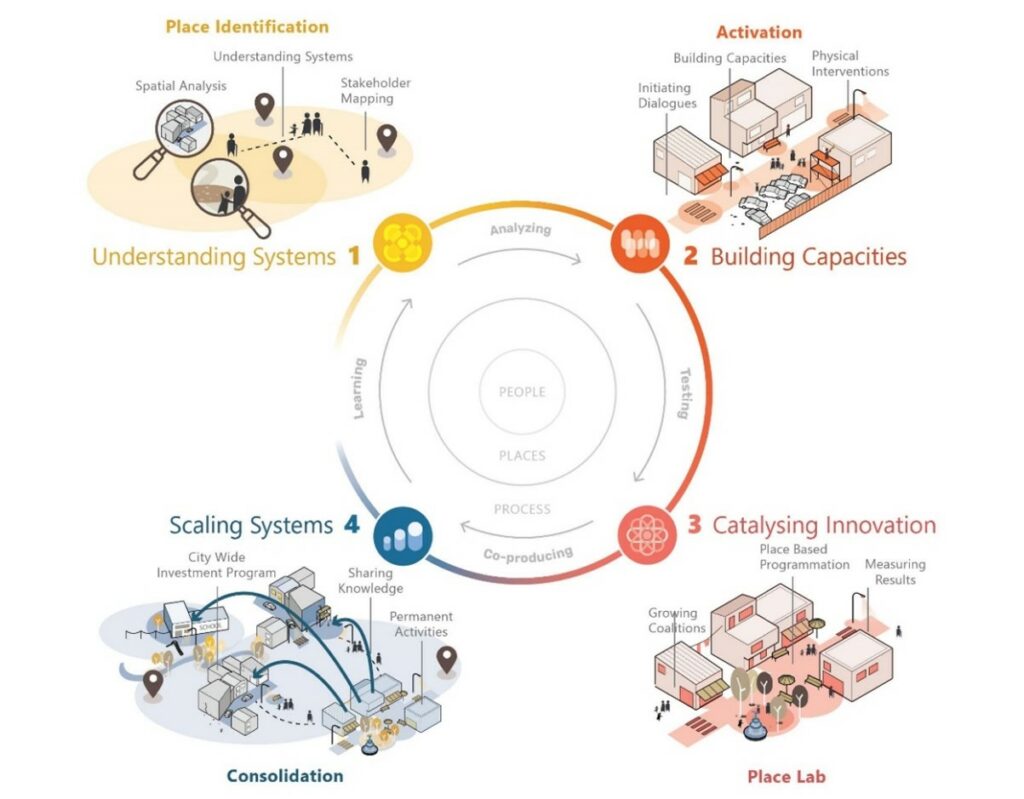

Where? International (Pilot cases in Envigado, Colombia and Bandung, Indonesia

What? S²Cities is an open and iterative programme based on a cyclical process of system understanding, building capacities, prototyping solutions, and improving and scaling solutions.

How? The S²Cities Programme aims to empower young people of ages 15 – 24 in cities to shape safer and more inclusive urban environments. By partnering with strategic advisors, learning partners, and local implementation organizations, the programme connects young people to the resources they need to become agents of change in their cities.

Since 2021

[2] De Potterij (https://buur.be/project/pilootproject-potterij-mechelen/)

Where? Machelen, BE

What? Vision creation and project direction of the Potterij site, a former laundry in the center of downtown Mechelen, in the framework of the Pilot Projects ‘Back in circulation’

How? OVAM has been fully engaged in the remediation of the site for several years and has high ambitions for the future: the development of a circular urban lab in and around the Potterij. Through a transition-oriented planning process this initial future vision at building level evolved into a supported policy vision at building block level.

Since 2016